*Skylark (Alauda arvensis)

ESP – ENG

HOW IT ALL STARTED

When I published my article on Silence last year, I discovered the work of Quiet Parks International. I immediately felt connected to its purpose. I continued my research, which led me to One square inch of silence, a book written by co-founder Gordon Hempton, in which the author travels around the USA in his van, Vee-Dub, loaded with his recording equipment and sound level meter, in search of the least acoustically polluted and most threatened places.

As he travelled on, I realised that the strict criteria he had set for identifying the last remnants of silence in the North American country were more than possible in the surroundings of Montañas Vacías: For him, the most valuable measure of the acoustic quality of a site is the time interval between man-made noise encroachments. In his experience, silences of more than 15 minutes were extremely rare in the USA, and almost impossible in Europe, except for some regions in northern Finland and Norway.

I was convinced that there was another area, a huge one, further south.

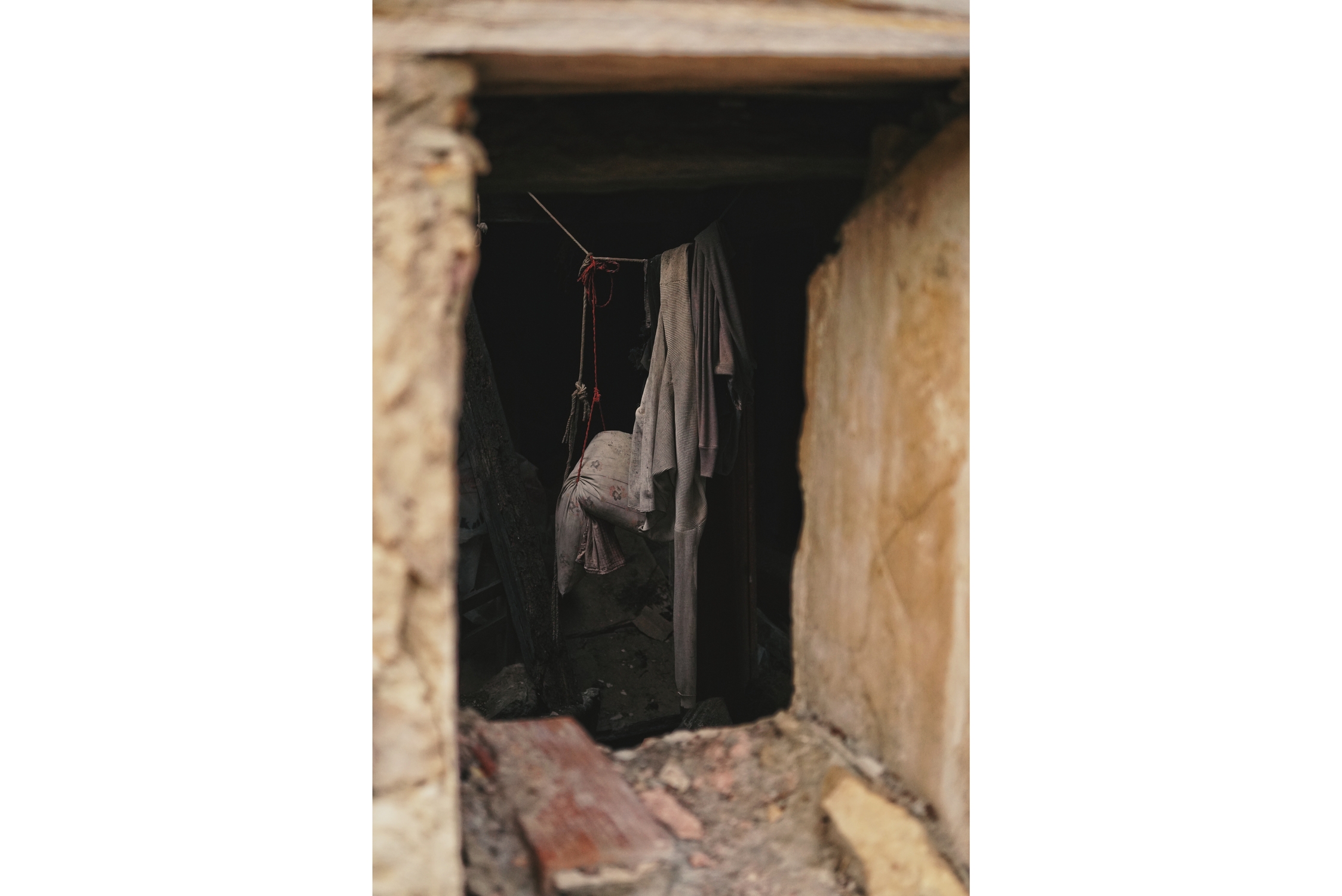

Both Gordon Hempton’s book and the material I discovered on the Quiet Parks website (QPI from now on) opened up a new dimension in my journey to preserve quiet in our area. I even took the plunge and bought a small recorder to take my first steps into soundscape recording, a beautiful discipline that reminds me very much of my first steps into photography.

(Some of my recordings in my Soundcloud profile)

A few weeks later, I felt the need to contact QPI, if only to thank them for this breath of inspiration, this step forward in my sensitivity to this great resource that I felt was so undervalued and neglected in my area. Always aware of my small size and the format of my project, because I am neither the manager of a natural park nor a powerful administration, just a crazy man with crazy ideas in his head.

That thank you message led to some initial email contacts and a series of video calls with Vikram Chauhan, co-founder of QPI with the aforementioned Gordon Hempton, and Nick McMahan, director of Quiet Trails, QPI’s division for silent routes. It was a very motivating process where we exchanged ideas, philosophies, learning, and where I could share my ideas about the demographic reality of the Spanish inland, its orography, its environmental value, but above all the quality of its soundscapes. This lack of noise is one of the things that travellers appreciate most when they finish MontañasVacías. It was undoubtedly something worth protecting.

«SOUNDPACKING»

To protect a resource you need to enhance its value, and to enhance its value you need to know it. QPI offered me the best way to progress in this learning process: riding for a few days with two real experts on sound, visiting some of the most emblematic places in MV.

ellas

Emily Hesler is A QPI volunteer sound recordist and USA representative from Upstate New York, currently living in Uppsala, Sweden. She works at MachineGames as a VO Designer, and freelances as a nature sound recordist, spatial audio designer, and composer.

Úrsula Bravo is an experimental musician and sound performer, dedicated to the study of soundscapes. She collaborates with the Biodiversity Group of the Azores and is developing an experimental sound lab to analyze soundscapes and increase our awareness of the land and other species.

Over four days of cycling along several sections of the route, we tried to get an idea of the true dimension of the acoustic value of these landscapes. Here, Nick McMahan, director of Quiet Trails, shares his perspective on the purpose and raison d’être of these acoustic journeys:

«Quiet Parks volunteers are an essential link in sharing experiential knowledge of quiet. The search for quiet and reflection of the sonic journey. A trip down a quiet trail aims to determine the value of the travelers experience. To be able to ask themselves and each other, “do we feel quiet at some point along this path?» Critical observation times are mornings and evenings, but listening and testing throughout the day are necessary to know the whole sound picture of the location.

The quality of sound in the environment is as much a sign of ecological health as anything can be. To have a meaningful observation of ecological acoustics you must take a journey. A journey of experience and contrast. For me this has been as important of an inner journey as an outer one. A search for quiet and solitude, but also a shared experience, allowing the space of the location to bring people closer to each other and closer to themselves.

Recording these places is a gratifying technical extension, not unlike photography or other art forms in a physical location. What does art do for the creator? What does it say about the place of conception? I hope these paths and trails can lead people to ask questions about our relationship with the earth and bring light to the importance of inner and outer commune we can experience in life.«

These are structured and methodical trips that follow a general procedure. In the words of Emily Hesler, it consists in recording for a couple of hours at dawn and dusk at every campsite, taking notes of disturbances as they occur: what the disturbance was, the level in decibels, how long it was observed, and how disruptive it was to the overall experience. Singular spots along the trail are also registered, such as where birds are particularly active and the birdsong is particularly noticeable.

THE RESULTS

Below, Emily and Úrsula share their thoughts on how they felt after riding and experiencing some of the roads of MontañasVacías:

EMILY HESLER

«The overall experience was audibly and visually very serene, peaceful, and almost otherworldly. It felt very separate from everything else, especially when considering that most of these areas were only accessible by biking.

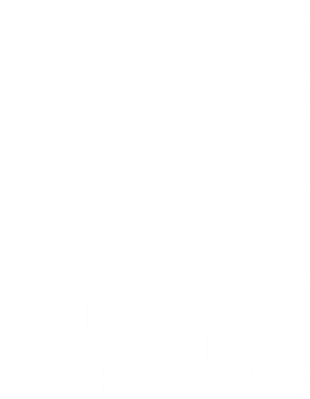

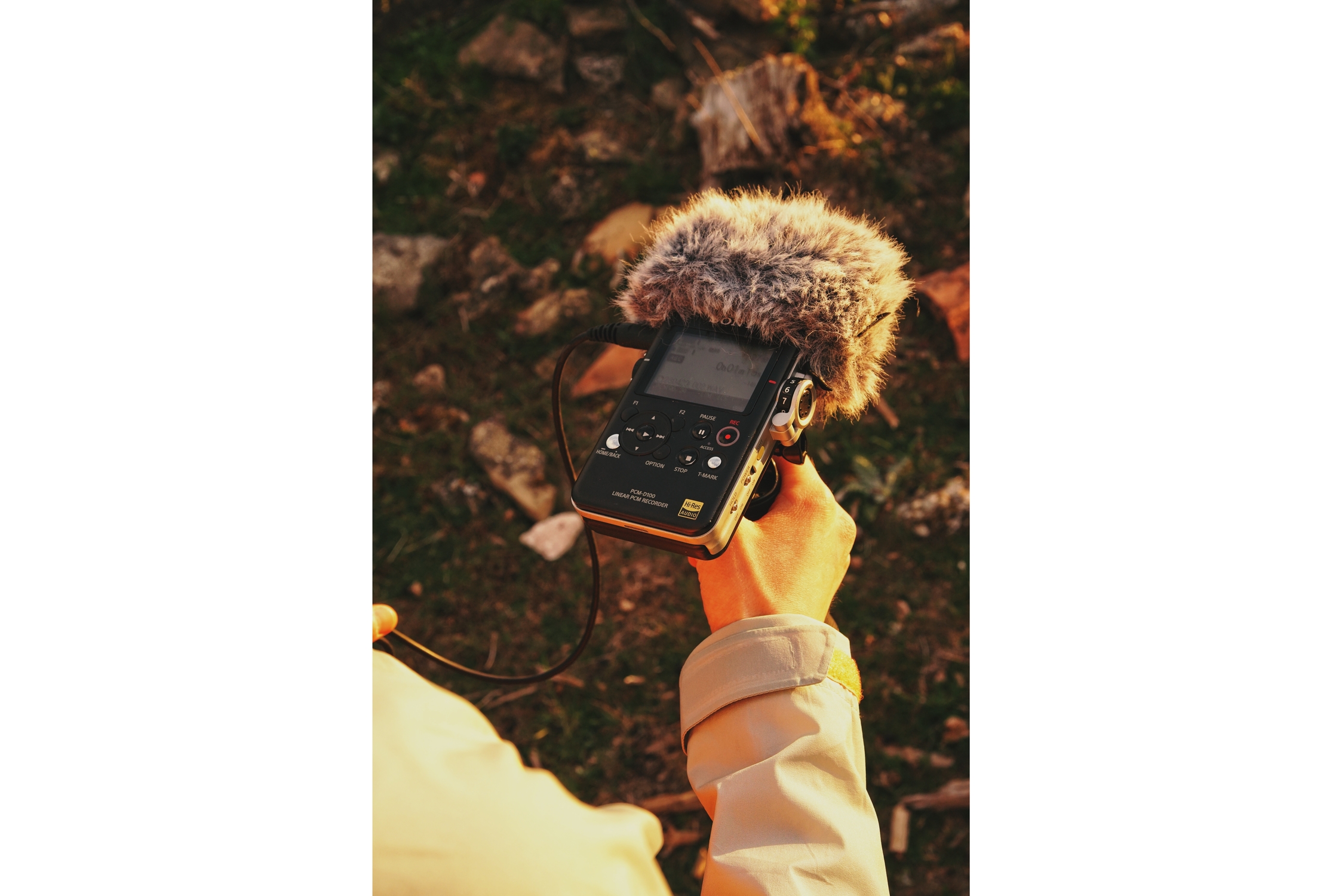

It was also quite the experience to camp in an abandoned stone village. It allowed for me to consider quiet from a different perspective, imagining how that village could’ve been busy and bustling just fifty years ago, or even sooner. It made me eager to explore more places like that, to see how nature and quiet have reclaimed areas that humans once settled in.There was a very noticeable contrast between these longer stretches of quiet and the small villages we rode through. Having these short periods of noise disturbances made me appreciate the peaceful sections more, and helped me to realize how still and serene those sections were.«

Some of Emily’s recordings:

ÚRSULA BRAVO

“Through visual observation of the territory, it was possible to identify interesting listening points, where we discovered that the acoustic properties of the geomorphology of «empty Spain» offered us an essential natural auditorium.

To be able to experience the richness of a natural space from each of the listening points that Ernesto chose for us from his itineraries, we were constantly reminded that we were exploring a hi-fi territory that presents a spatiality marked by the orographic composition. In this environment we could hear sounds far away from us, despite the presence of others in the foreground. Each sound was clearly distinguishable, because each acoustic event follows its own sound/silence cycle (each sound emission is followed by a pause), a dialogue was established with the physical environment. It can therefore be said that each sound has its own rhythm and can occupy its own sonic niche. A healthy and respectful space where all species have their space to communicate. In low-fidelity areas, the expectation of being able to feel the great natural orchestra disappears when masking takes place, the high decibels provoke the massive rejection of mammals, birds, insects… they hide from us. Another characteristic of the hi-fi landscape is that it is largely made up of low-intensity sounds, whose decibels are at a threshold that is comfortable for the nervous system.

Just as we look for the best visual conditions to enjoy a good sunset or sunrise, these exercises, this quality seal, will give us the opportunity to remember old ways of relating to the natural environment, to be more honest about our needs, to empathise with those of other species and to be able to make better collective decisions to take care of the territories offering ecotourism as a regenerative way. Quiet is the new cool».

Some of Úrsula’s recordings:

MY LEARNINGS

Being able to count on people with such international experience throughout the process has allowed me to discover different points of view, learn about other projects and experiences in different places. Here is a summary of some of my learning in different areas.

Sanctuaries

In a life saturated with bustle, stress and crowds, environments and experiences where natural silence is protected are of enormous importance. Their positive effects on physical and mental health are beyond doubt. As Hempton mentions in his book, they can be considered true «sanctuaries of silence».

For many, MV has meant an experience that goes beyond the journey, beyond mere cycling, considering it more as a space of retreat, of reconnection, of total communion between the visitor and the territory through its landscapes and inhabitants, where silence and solitude are its most outstanding values. An inner journey whose concept has been shaped by the travellers’ own experiences over the past few years.

Furthermore, promoting the conservation of these natural sanctuaries is the best way to protect their wildlife and habitats, and a great opportunity for their inhabitants.

Awareness

It is therefore necessary to learn that we must take care of this acoustic heritage in the same way we protect architectural or environmental heritage, and to be able to identify its threats in the same way that we know how to identify those that threaten, for example, the cultural heritage of our villages or the ecological value of our forests.

We may all be able to recognise the damage caused by graffiti on a historic building or the litter in a forest, but we have yet to make progress in recognising the real damage caused, for example, by playing music too loudly in certain natural environments.

Administration

We need brave administrations in this respect. They must understand silence and its conservation as a resource for our communities, a sign of identity. But also as an opportunity for the future.

Some simple measures could be:

- Promote the creation of non-motorised routes that allow walkers, horse travellers or cyclists to enjoy a quiet experience, protect certain places from overcrowded tourism and reduce the risk of forest fires. Of course, it must be properly regulated to allow authorised vehicles, professionals, guards, etc. to pass. On my recent trip to Scotland and England, I rode hundreds of kilometres on unpaved, traffic-free roads, and the feedback I received in the villages was overwhelmingly positive.

- Another simple measure would be to avoid «over-asphalting» natural roads with a high natural richness. There are some recently asphalted roads, or in the process of being asphalted, which make some very valuable sites too accessible, without a clear function of communication or linking sites. Especially when there are villages nearby with access roads in poor condition where such tarmac would be welcome.

- Awareness campaigns. You only love what you know, and today there is still a long way to go in recognising natural silence as an endangered resource. It wouldn’t be too difficult to incorporate acoustic respect messages into other existing awareness messages, such as fire prevention, litter-free spaces or respect for flora and fauna.

- Vigilance and control. Steps must be taken to control activities that threaten this resource, such as music played too loudly in natural settings or at inappropriate times. And if such rules already exist somewhere, push for them to be followed.

- Better decisions. Taking account of one of your most valuable and endangered resources can be the best decision-making tool for new infrastructures, projects, deployments, etc.

The visitor profile

Enhancing the value of our acoustic wealth is a tool that also allows us to shape the visitor profile in a certain way, something that is really interesting for our villages and natural environments. It allows a greater emphasis on quality rather than quantity. The number of visitors doesn’t matter, what matters is the positive impact on the area. We often read headlines about the number of visitors to some natural environments, but we don’t really talk about whether it’s really what the conservation of that place needs, nor about the real economic impact on the villages in the area.

A more specialised and aware visitor profile is less seasonal, more spread out throughout the year, but also more spread out across the territory, taking visitors outside the usual ‘honeypots’. Proof of this has come over the last five years with the arrival of bikepackers from all over the world for most of the year, even in low season, visiting places not normally reached by traditional tourism.

It is clear that the process of raising awareness of the need to preserve quiet in our natural environments can be very complex, and creating new inertia and habits in society can be frustrating, that getting administrations to act is not easy and even less quick, but that’s why it’s important that we all do our bit to promote and spread these values. May we be the change we wish for the world. Only by raising social awareness of the importance of natural quiet can we increase the chances that steps will be taken to protect it in the medium term.

SUNRISE

While my ‘Acoustic Expedition’ mates made their final recordings in the first rays of sunshine, I took the opportunity to take some photos, play with my recorder (a mere toy compared to their equipment) and spread out the tents to dry in the sun. When they came back, I couldn’t hide my excitement to hear their impressions of what they had recorded. Each breakfast was a real masterclass for me.

Thanks to them, I have adopted the phrase: «The more you listen, the more you hear«. In the same way that when I learned photography I began to look rather than see, the more I pay attention to what I listen to, the more information I hear. I find that I’m now much more sensitive to details of sound that I hadn’t noticed before: I begin to notice different nuances in the wind as it passes through different types of trees, I pay more attention to the songs of birds, or I immediately notice that distant airplane or motorist that was previously unnoticeable.

At breakfast, Emily, Ursula and I agreed. It had been one of the most beautiful sunrises of our lives. The environment, the warmth of the light, the solitude, yes, but also for what we have almost never noticed, that secondary actor, until now: the soundscape. Lets give it the value it has and protect it before it is too late and these last sanctuaries of silence disappear completely.

Complete Photo Gallery

*Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos)